Artist Marianne arrives at a remote chateau on an island off of Brittany, where she’s to paint a portrait for an aristocrat’s daughter to send to a potential husband. A previous portraitist failed to complete the commission due to his subject’s recalcitrance. Marianne is tasked with acting as young Héloïse’s companion, while painting in secret at night.

Artist Marianne arrives at a remote chateau on an island off of Brittany, where she’s to paint a portrait for an aristocrat’s daughter to send to a potential husband. A previous portraitist failed to complete the commission due to his subject’s recalcitrance. Marianne is tasked with acting as young Héloïse’s companion, while painting in secret at night.

Héloïse, freshly sprung from the convent, has lived her life repressed in every way. Her home is barren of books (she demands to read the one book Marianne has brought with her) or music (a harpsichord is covered and hidden away in an unused room). At her first opportunity to take a walk outdoors, she runs the edge of the same cliff where her sister recently jumped to her death. When her panicked companion catches up to her, Heloise says, “I’ve dreamt of that for years.”

“Dying?” asks Marianne.

“Running.” Héloïse answers.

She is resentful that she is expected to act as a substitute for her sister’s arranged marriage. Marianne asks Héloïse if she is sad about her circumstances. “No, angry,” is the young woman’s answer.

It’s inevitable that these two young women, living in isolation except for a young maid, grow close. What’s more, Marianne’s honesty with the younger woman, admitting that she, as an artist who will assume her father’s business one day, cannot understand the prison of privilege that Héloïse endures. She also confesses to the surreptitious mission she’s been hired to execute It’s the first time the younger woman has been treated as an equal. So it’s not entirely surprising when the two young women’s isolation and intimacy grow into a physical passion.

The difficulty of writing about an artist is that she is more about looking than talking. Long scenes of the two women gazing at one another convey the seductive pull of truly being seen by someone. A scene of local women’s gathering one evening is a turning point. Aroused by the group’s singing and dancing by firelight, a slow burn becomes a conflagration, and that night, Marianne and Héloïse make love.

But this love story has no happy ending. Héloïse’s mother returns from her travels, Marianne completes the portrait, and Héloïse is married off to her suitor.

Some scenes evoke the world as women might like it to be. Marianne’s portraits do not resemble the style of the late 18th century. (Although her contribution to the Paris salon depicts the myth of Eurydice, typical of the accepted salon style.) Rather, they look forward to an era a century later, when portraits were less idealized and conveyed a subject’s interior life. And, in the film’s fantasy world, women attend the symphony alone, without escort or chaperone, sans wrap or reticule.

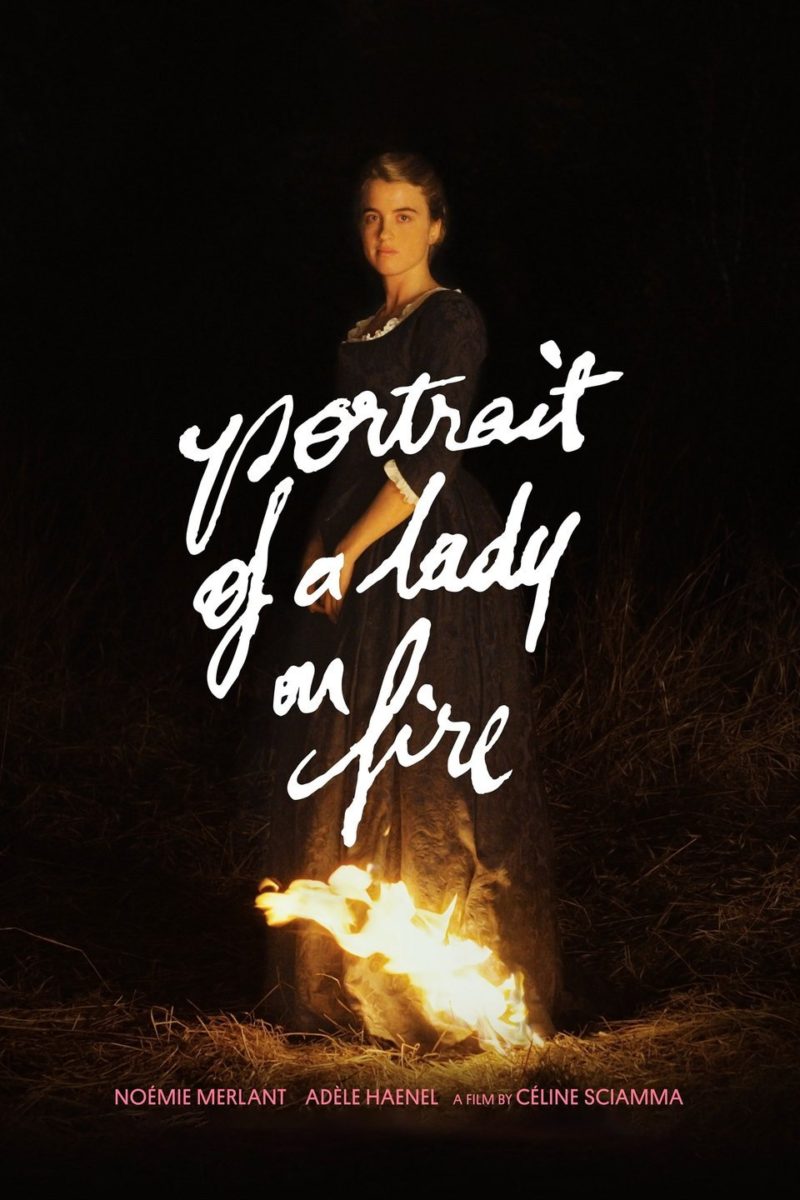

I wonder why the title of this film, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu, is mistranslated as Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Neither of the two main characters is a lady in age or status. Portrait of a Young Girl on Fire, the correct translation of the French title, perfectly describes Héloïse, a young, sheltered woman whose repression and rage make for a combustible combination.